A historic therapeutic contact lens

Series on the Roth Collection

Contact lenses are not only a valuable visual aid, they were also used soon after their invention as a bandage and, following the successful synthesis of water-retaining plastics, as a drug carrier on the eye. Their ability to compensate for irregular corneal astigmatism was recognized as early as the first fitting attempts at the end of the 19th century. Their orthokeratological effect, comparable then to a corsage, was also able to help stop keratoconus or to smooth out a corneal scar.

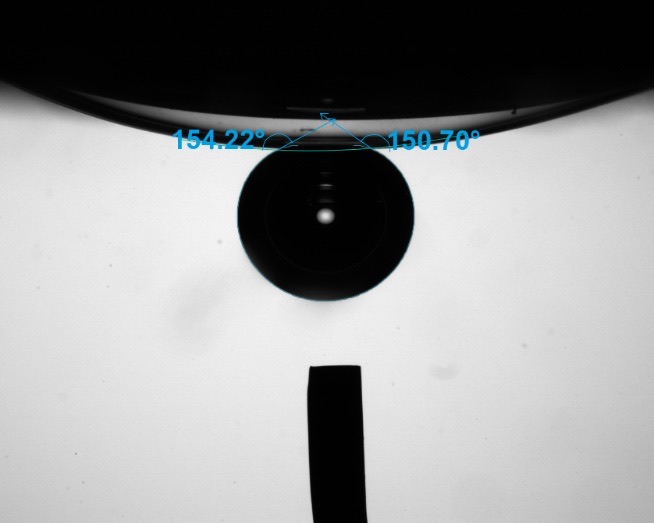

As part of the first, mostly experimental adaptations, the possibility of exerting slight pressure on the cornea while wearing them was discovered towards the end of the 19th century. This could be used to eliminate a superficial defect in the cornea. Even before the first slit lamp or ophthalmometer was constructed, it was known that only a cornea with a central spherical shape enabled optimum visual acuity, whereas irregular astigmatism led to image distortion.

It was discovered that a glass scleral lens up to 20 mm in size at the time was suitable for smoothing a pathologically deformed corneal surface and thus optimizing visual acuity, but that this effect disappeared again within a few hours when the lens was removed from the eye. All so-called orthokeratologic properties proved to be only temporary in the long term. Prolonged lens wear was therefore necessary to achieve the therapeutic effect.

This was problematic because the wearing time of the first contact lenses was considerably limited. If they were on the eye for several hours, there was a lack of oxygen in the tear lens. The onset of anaerobic glycolysis led to the accumulation of metabolic end products such as lactic acid in the tear. The consequences were pronounced corneal edema and irritation of the anterior segments of the eye, increased lacrimation, reduced visual acuity and increased sensitivity to glare. The only solution now was either to reduce the size of the lens or to adapt its design more optimally to the corneal surface by means of aspherical inner curves. It was also necessary to optimize the oxygen permeability of the material. However, this required decades of further development.

Drilling the perfect perforations

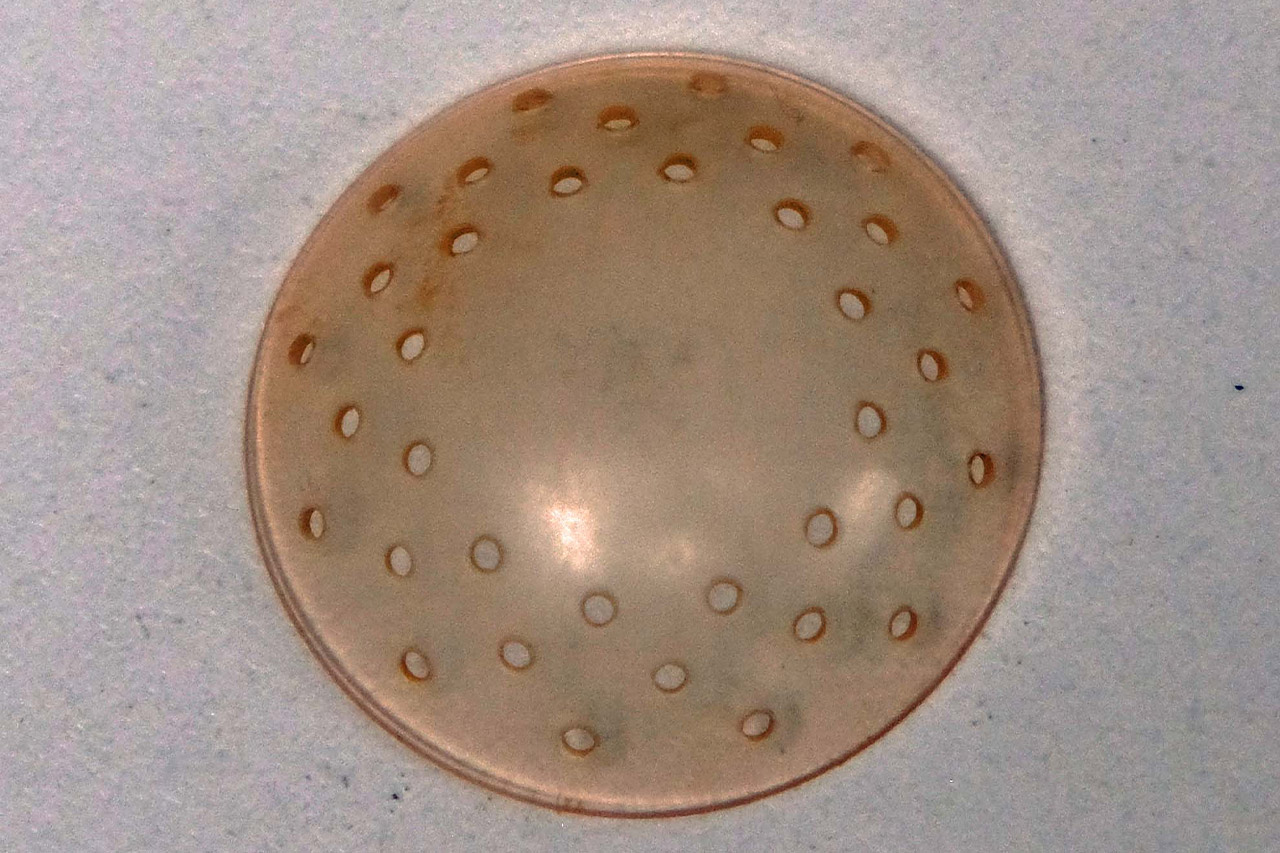

It was therefore ingenious to simply drill through the lens in order to optimize tear convection. This was difficult to achieve with glass lenses. It was much easier later with the rigid lens material, PMMA. A hard metal drill from dentistry was used to drill through the transition zone of the lenses and deburr the holes. But the diameter of the perforations also had to be right: if they were too small, they became clogged with mucus and cell detritus from the tear fluid; if they were too large, the fit of the lens became unstable and it slipped or even fell off the eye.

The 14 mm lens shown here is one such therapeutic lens from the early days of contactology. Its exact date of manufacture is not certain, but it probably dates from around 1930. A total of three rows of staggered perforations, each with a diameter of 0.3 mm, improved oxygen saturation at the cornea.

From 1964 onwards, it was possible to dispense with such perforations in the contact lens, the soft lens plastic allowed an almost unlimited wearing time due to its better oxygen permeability and the now successful reduction in center thickness made the contact lens a suitable bandage. The soft hydrophilic contact lens in particular can now be used as a bandage in the event of a corneal injury. Another property of modern lens resins is their storage behavior, which means that the lenses are also suitable as medication carriers.

Perforated scleral lenses are now only fitted in special cases. The lens shown here is undoubtedly one of the very first contact lenses for therapeutic use. It comes from the practice of a colleague who has passed away in the meantime; he had kept it carefully for many years for possible reuse.