Erik Larson: The Problem Solver

A visit to Larsen Equipment Design

Together with his son Andrew, Erik Larsen shoulders a steel bar and carries it into his workshop. It smells of oil and metal here. A whole battalion of machinery is installed here. Large, old, new and small. And the really big ones, which easily have a footprint of 6 m² and reach far over the heads of the employees who operate them. Countless boxes of machine parts, screws, cables and the many components needed to build his blockers and polishers and other products are lined up here. We visit Erik Larsen. He opened the door to his workshop in Seattle for GlobalCONTACT and gave us a tour.

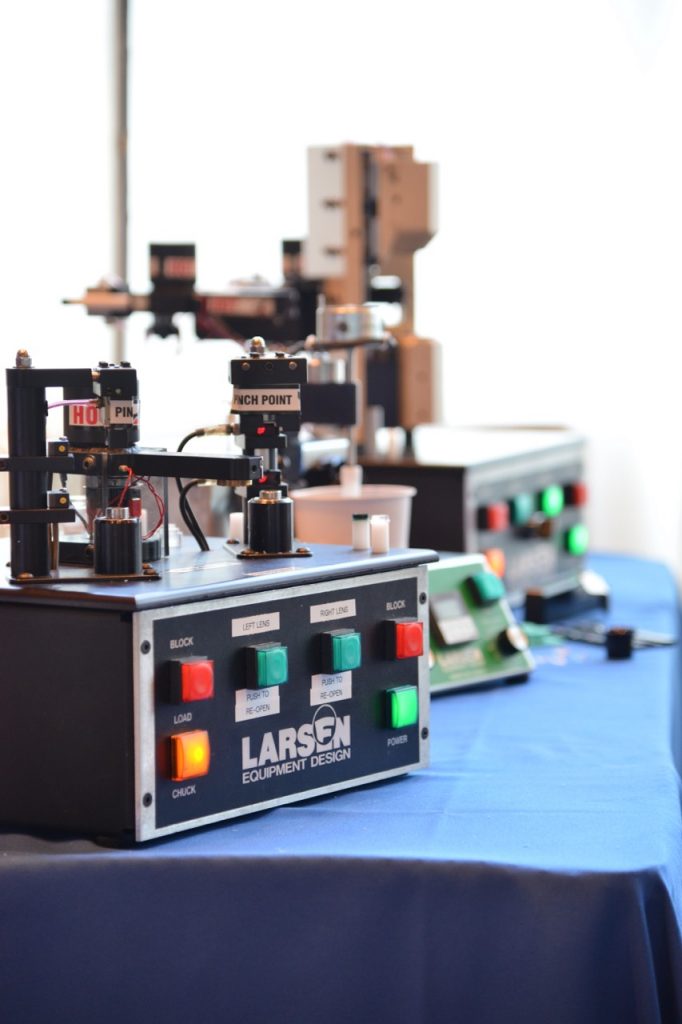

A row of auto blockers sits on the large workbench in the middle of the workshop. They are being assembled here and are not yet finished. One by one, the employee responsible for the electronics has to lay various cables and connect them to the electronics. This device is one of Erik Larsen’s bestsellers. But his polishers are also known all over the world in contact lens manufacturing.

A world map in the workshop marks the places to which his machines are delivered. It contains many pins that testify to the success story of the family business Larsen Equipment Design (LED). In the past there were many, many pins in North America, today there are few.

“In the 1970s, there were once around 500 labs in the USA – today there are only 15,” says Erik. What would be a difficulty for other companies, the globally-minded and inventive engineer has turned into a success: today, 90% of his turnover is generated outside North America.

Since his beginnings in 1981, he has been thinking internationally and he soon looked over to Europe and showed his machines at the European EFCLIN conference.

The beginning: An engineer through and through

Let’s start at the beginning: Erik Larsen was born with a love for mechanical engineering. He was raised in a mechanical environment. He had his first “playground” in the workshop of his father, a boat builder on Vashon Island, where he was able to create things and took great pleasure of it. There he learned early on what it took to get things done. Later he graduated at the University of Washington as a mechanical engineer.

He initially worked for a few years at a company that manufactured contact lenses as well as its own machines for the emerging contact lens industry. “At one point they got bought out by CooperVision (Medi-Cornea) and stopped producing machines. But I loved making machines, so I quit and started LED about six months later,” recalls Erik.

The leap into independence

During his time as an employee, he had already made numerous contacts. He developed a 6-spindle polishing machine and took that to the CLMA congress in 1982. But at first he didn’t receive a single order. “There wasn’t much money involved and it was just a try – but I knew I could do it,” he recalls.

He waited and didn’t hold out much hope at first, but the discussions and the presentation of the machine paid off. After around a month, the first order came in. He had obviously been remembered. Even though he hadn’t even brought a business card with him, let alone thought of a suitable marketing concept. More orders came in over the next few months. His former boss also ordered six machines. Finally, Bausch+Lomb ordered a set of machines. But that was just the start, as numerous orders followed. The six-spindle polisher was awarded the first patent for Larsen.

Inventiveness and precision

At that time there were five companies that also made contact lens machines, so there was competition. After a short time, he got a call from an employee who worked at Wessley Jessen and placed a large order. It was George Glady, who was working there at the time.

“Looking back now, I can say that B+L had provided us with an income, but George Glady turned LED into a thriving business”.

Later Wesley Jessen was bought by Ciba Vision, which then became Alcon – and today LED ist still working with Alcon in addition to B&L. George Glady, on the other hand, later founded Euclid Systems and Erik continued to work with him. Sadly, George Glady passed away in the fall of 2023.

The road to the world stage

Over the years, Erik Larsen developed a family of polishing machines in various sizes. And in 1990, the lathes were developed to produce ‘freeform optics’. “I was approached to develop a polisher for aspheres and torics. It seemed they needed someone who could solve the problem. So, we did!” he recalls. The “bladder polisher” was awarded a patent.

For beta testing, he took his bladder polisher to a small trade show in Las Vegas. He met with Larry Nygren from Custom Craft Lens Services. The reason was that Larry Nygren was using a state-of-the-art lathe from Opto-form at the time. “I wanted to see if the bladder polisher would change the lens instead of just polishing it. It was a good test: we ran about 20 lenses through it and then he started packing them,” he recalls. “I said, ‘You can’t do that, you don’t know if they’re any good!” He said, “Oh no, they’re gorgeous!” He shipped the lenses out of that prototype polishing machine. He said, “This is going to change the industry.”

Attention to Detail

A few years earlier, Erik had started publishing articles for Wim Aalbers (the former publisher) in GlobalCONTACT. Always with his perspective of a mechanical engineer in contact lens manufacturing. “Shortly afterwards, my younger brother and I went to an EFCLIN conference in Brussels for the first time and we took our machines with us. But the people were first pretty skeptical about it because they were using different tools”, says Erik. “They thought everything had to be converted to our system. So we brought a 6-spindle-machine with 6 different spindles. And the first came and said: ‘we can’t use that!’ Well, we showed him a tool and said: ‘maybe your tool looks like this? We can make it for you then’”. That’s when many people realized that Erik adapts his machines to his customers’ requirements and not the other way around.

Erik Larsen is his own brand. His machines sell because they are so customizable and easy to integrate into the production process. He didn’t achieve his success with a sophisticated marketing plan or fancy presentations. He is an honest soul and simply says what he does. He remembers: “In the mid 1990’s I went with my wife Pam to an EFCLIN Show in Amsterdam and I had to prepare a presentation. I remember I was very nervous to prepare my speech, since I am not the kind of guy who likes to be on stage. So Wim Aalbers, who then also was Executive Director of EFCLIN said: ‘Just tell us what you do…’ and that got me talking. So after that we picked up the European market really well.”

However, not all machines were always a success, “We also had a few flops,” he recalls. These setbacks were always an incentive for him not to give up. Different processes with different levels of automation, for example, always require adaptation. We have learned from this and then offer customized solutions.

Built to last

Today he offers 6 different models of Blocker, 4 for Contact Lenses and 2 for IOL. Depending on how they make their lenses. “We are the only ones who do that,” says Erik. The differences depend on how the specific company manufactures its lenses. “We have to look at that and get an idea of how to solve the process problem. In the last few decades, the main challenge is process, but the industry is maturing to standardization. This is ironic since in contact lens production, each lens is unique. We offer machines and processes that are ‘immune’ to the variation in product. Sometimes it takes a whole month of consultation before we fully understand the process and offer an appropriate machine,” he adds. “Sometimes people joke: ‘Erik, your machines last too long!’ That is nice to say but the fact is: good design lasts. They’re supposed to. I know there are some of my polishers that have 50,000 hours on them.” However, it is also important for him to mention that there are constant updates for many older machines, which should also be used.

He sees the advantage of his machines as being able to maintain them oneself. “We can train people to take care of it on site,” he says. Spare parts are supplied with the machine or can be delivered within a few days. He adds: “It makes a difference if a lab has to call in a factory technician for a repair job for $5,000-10,000 or can do it themselves via video call. It saves time and money. You can also install the device yourself; you don’t need a person to come in externally – and that’s a very big difference to others.

Family business

He has built all of this up together with his wife Pam Larsen. They have been married for 43 years. And she has accompanied and supported him on his visits to CLMA and EFCLIN. Her realm at LED is often behind the desk. In the workshop, a room with windows separates an office. Pam Larsen (CFO) takes phone calls, answers e-mail and has a laugh with the staff. This is also where Erik’s drafting board is located, which today looks somewhat deserted. This is because the company has long since switched to creating everything digitally. His daughter-in-law Stephany and his son Andrew also help with this.

The order situation is currently so good that the company is desperately looking for new employees. However, like everywhere else in the world, the shortage of skilled workers is also a problem in Seattle. The 2X increase came during the coronavirus pandemic. He interprets it as follows: “After a drop in orders at the beginning of the pandemic, many companies apparently took advantage of the shutdown, so that they renewed or modernized their production facilities and needed new equipment, which then came a year later – and that benefited us. We saw a huge increase in business from 2020-2021, and it’s still growing.”

LED has undoubtedly occupied a niche with his devices. We want to know if they have never been copied? “Yes, I know of a few occasions.” he says. “And although some of the maschines were copied, yet they didn’t perform particularly well and needed to be rebuilt in a few months.”

One manufacturer had bought one device and then made several copies. When Erik visited him, he asked him: “Are you in the machinery business or the lens business?” “Well,” he said, he was in the lens business. Erik replied: “The machines you copied are 25 years old. Are you interested in state-of-the-art machines?” He regards his customers as partners. Partnerships come with advantages such as access to new products and technologies. “We grow together.”

In the end, he reordered their machines from Erik Larsen. In most cases, this didn’t really turn out to be a disadvantage for LED, because in the end the orders did reach him.

The future

Automation has been playing an increasingly important role for some time now. This presents many companies with a number of hurdles. “I’ve already seen a lot of changes. The lens designs and manufacturing possibilities are fantastic today!” he reports. “Although the push to automation is still not an easy thing to do. The big hurdle is: once you get it installed, who is going to maintain it? When you drop a lens, you pick it up, but if a robot drops it, it doesn’t know what to do. So there needs to be an advancement in technology.”

Adding to the earlier partnership comment, product development does not operate in a void: “We get most of our ideas from customers that need a solution to a process problem. It’s a collaborative effort.”

He adds: “The fact is that after University, there were many opportunities in the Seattle area. But I chose to go out on my own. We created a culture of product/process development, reliable products, customer service, and innovation. Even when I cut back to a few days or a week, the team is in place to grow the company. Our customers expect great things from us. With our core team in place we are in good shape,” says Erik happily. His 35-year-old son Andrew wears a few hats including building blockers, purchasing, and shipping. Together with a well-coordinated team, they have been working together for years. As of this publishing, they addes two more empoyees who are working out well.

When Erik Larsen stands among all the machines in his work coat in his tool shop, he is very aware that they are making a major contribution to helping millions of people achieve better vision every day with the development and manufacture of his machines. “We are proud to be part of this industry and to work with companies that develop these excellent lens designs and ultimately ensure that it helps people of all ages to see better and certainly changes many people’s lives.”