Going backstage with scleral lenses – a star is born

A trilogy on specialty contact lens safety – part 1

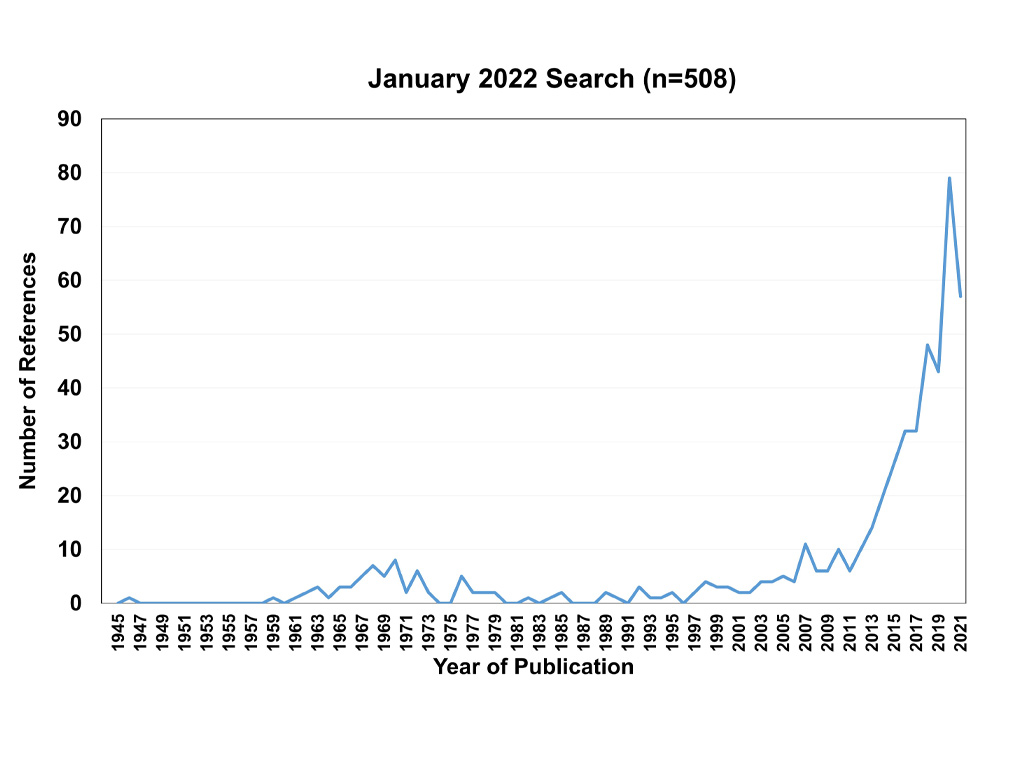

Looking back 30 years, it is no secret that probably one of the biggest surprises in our industry has been the re-emergence and development of modern scleral lenses. The surge of scleral lens publications demonstrates their incredible increase in the recent peer-reviewed literature. Truly, ‘A Star Is Born’, like in the 2018 American romantic drama with and by Bradly Cooper and featuring Lady Gaga. Interestingly, though, this is the fourth filmed version of that story after the original 1937 and 1954 American musical (starring Judy Garland) and another 1976 musical.

The comparison with scleral lenses is striking: after small successes in the 1960s and 1970s, modern scleral lenses have now made their great comeback too – with bells on and to never go away again, it seems. What has caused this surge, and how safe is scleral lens wear?

Tip of the eyesberg

The success of the modality in large part has to do with a better understanding of ocular surface shape. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) turned out to be an extremely helpful tool, as it soon was discovered that the transition zone from cornea to sclera was ‘not all that curved at all’ but rather tangential in shape (a straight transition in many parts of the globe at least). Traditional textbooks had to be rewritten. In addition, although known through clinical wisdom by some, it was found that the ocular surface beyond the corneal borders was quite irregular (and increases in irregularity toward the periphery). And the term ‘height’ has since been used increasingly in the contact lens industry to replace ‘curvature,’ which is a game changer. Today, we can classify the sclera into different categories based on shape [1]. It can quite easily be assessed now when to start using back-toric-haptic scleral lens designs and more complex back-surface designs. Clinicians around the world agree that if you align the scleral lens better with the ocular surface, fewer problems arise and the chance of scleral lens success increases.

So, while the surface of the eye is quite well understood now – and this part of the puzzle is practically ‘solved’ – this was, literally, just the tip of the “eyesberg” regarding scleral lens wear. What is next is: What is happening behind the scleral lens during wear? Let’s go backstage on the set of ‘A Star Is Born,’ the scleral lenses edition. Everybody who has been backstage at a concert or anything like that knows that it can be somewhat messy and chaotic there. Let’s see how messy it is with sclerals and where we stand.

Oxygen debate

Since the introduction of scleral lenses, there always has been a debate about suboptimal physiological conditions beneath the lens and the potential for inflammation and infection with the modality, as first, the oxygen delivery to the cornea is hampered by the fact that the scleral lens is much thicker than a rigid corneal lens (by a factor of about three), and second, the fluid layer behind the lens works as an extra filter (with an estimated Dk of 80). In essence, therefore, scleral lens wear can be likened to a piggyback system with two barriers [2]. Furthermore, there seems to be hardly any tear film exchange possible behind a scleral lens, which obviously is different from tear exchange with a rigid corneal lens.

Only recently, with the surge in scientific publications, has this topic been well documented. Work by Damien Fisher BAppSc, PhD, presented in the scleral lens supersession at the Global Specialty Lens Symposium (GSLS) and in the International Forum for Scleral Lens Research (IFSLR) 2022 in Las Vegas, showed that, contrary to previous beliefs, if the Dk of a scleral lens exceeds 100 units, then the oxygen delivery to the eye needed for normal functioning in daily wear is met in most cases. Lens thickness and lens reservoir variations help in providing more oxygen, but only if those variations are significant. [3] Lens fenestration, although potentially helpful in other ways, does not add much in terms of oxygen delivery to the cornea. Only in cases of compromised corneas (such as post-corneal transplant, post-radial keratectomy, etc.) can oxygen issues arise, but typically not in normal corneas.

What (about) the fog?

A nuisance at best for sure is a phenomenon that is unique to scleral lens wear: midday fogging (MDF) [4]. It deserves a place in this overview; however, it does not seem to pose any risk with regard to safety. It is a risk, however, for scleral lens failure in terms of dropout. Maria Walker in her PhD work – also presented at both the GSLS and the IFSLR – showed a couple of things: there seems to be hardly any difference between the observance of MDF at day one in subjects versus at day four. In other words and to simplify things, ‘you have it or you don’t’, in a manner of speaking. She also looked at subjective versus objective MDF scores and found the two to be highly correlated. What this means is that if patients complain of MDF, we can also see it behind the lens. The ‘seeing’ is best documented using OCT if available, as this instrument can show the particle density behind the lens [5]. The correlation between objective and subjective scores was highest, though, for the low grades of MDF; for the higher grades of 4 and 5 (out of 5), that correlation was much weaker.

The British Contact Lens Association (BCLA) CLEAR paper (Contact Lens Evidence-Based Academic Report) on sclerals advises to manage MDF as follows: decrease corneal clearance, improve landing zone alignment, treat underlying ocular surface disease including allergies and dry eye disease and use a more viscous application fluid. And if all of this fails, then lens removal and reapplication once or sometimes twice daily is recommended. A nuisance for sure, but it does not pose any additional risk. It does show that tear replenishment behind the lens is minimal, though.

As a little side-step: conjunctival prolapse is another adverse event that is new and unique to scleral lens wear. The conjunctiva is ‘sucked under’ a portion of the haptic portion of the lens. Recent studies from Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane (AU) found that ten participants showed conjunctival prolapse 22 times (37%) [6]. All participants were asymptomatic, with no signs of ocular redness/irritation. Nasal prolapse was more prominent than temporal, and the prolapse had a mean elevation of ~71 μm. While, again, this is not the biggest concern in our practice, it surely is a nuisance as well, and the flap can adhere to the cornea in some cases (in which case it does become a serious adverse event). As with fogging, one of the proposed mechanisms to prevent this from happening is to improve landing zone alignment.

Inflammation

What if there is tear stagnation behind a scleral lens? Is that worrisome? Investigators from Spain and Portugal conducted two important studies to investigate this. Gonzalo Carracedo et al [7] measured the ocular surface temperature on the eye during scleral lens wear in keratoconus patients. With inflammation, an increase in temperature can or should be observed. But no such thing was found: the patients wore the scleral lenses for six to nine hours, and scleral lens wear did not seem to modify the ocular surface temperature despite the presence of the tear film stagnation. Rute Macedo-de-Araújo et al [8] looked at the differences between inferior and superior bulbar conjunctiva goblet cells in scleral lens wear. Scleral lenses rest on the scleroconjunctival region, which could result in a mechanical impact on the bulbar conjunctiva that can hypothetically modify some properties of conjunctival cells. But they didn’t: there were no differences in goblet cell count or in goblet cell density, and it seems that scleral lens wear does not affect the density and secretion of goblet cells.

Microbial keratitis

What about the most important potential adverse event in contact lens practice: microbial keratitis (MK)? The topic of safety in specialty lens practice was part of a large session at GSLS, with coverage of that in the April edition of Contact Lens Spectrum [9]. In essence, a keratitis is an inflammation of the eye, but in this case some type of micro-organism is the cause. Only 15% of the eyes developing an MK in contact lens wear (any type of lens) will experience permanent vision loss, but depending on the condition and the type of micro-organism, an MK can have quite a devastating outcome for the cornea and patient.

Scleral lenses do not seem to pose an exceptionally large risk of corneal infections, Melissa Barnett OD, FAAO, FSLS, FBCLA, reported at the GSLS, quoting from the CLEAR paper on scleral lenses. [10] It is not easy to put a hard number on the incidence rate of MK in scleral lens wear, no matter how much we would like to communicate that to patients in practice. Despite the success of scleral lenses, the vast sample sizes needed to provide any serious numbers on incidence rates – which involve hundreds of thousands of lens wear years – are simply not available. And a complicating factor with this category is that underlying pathology is often present. Even in standard keratoconus, the epithelium is thinned and the cornea is more vulnerable than in the normal eye, but this vulnerability increases with different diseases, dystrophies and certainly with ocular surface disease conditions— and the risk of MK may also be increased.

One 2014 paper by Shorter et al [11] found the risk of MK with scleral lens wear in ocular surface disease to be 33 per 10,000 patient years, but with a large 95% confidence interval between 5.8 to 182. However, the balance of risks versus benefits in scleral lens wear almost always turns out in favor of the modality—as patients simply have inferior vision without scleral lens wear.

As stated in the April 2022 Contact Lens Spectrum article on lens care in specialty lens practice, while special attention to lens care seems to be warranted for any lens modality, special lens care for scleral lenses must be advised. In other words, hygiene with lens handling is crucial to improve scleral lens safety, perhaps even more so than material Dk considerations. Barnett at GSLS also reported that difficulty with lens handling is greater with scleral lens wear (63%) compared to with rigid corneal lens wear (40%) and that handling issues are the primary reason why scleral lens wearers drop out. [12, 13, 14]

IOP

Finally, there is the concern about a potential increase in intraocular pressure (IOP) with scleral lens wear. Again, this concern has been raised since the first reports on scleral lenses in the 1960s. In the previous edition of GlobalCONTACT, an entire article titled ‘Under Pressure’ was devoted to this topic. To summarize, there is a beautiful but delicate balance between the amount of fluid that is produced by the ciliary body (which is located at the base of the crystalline lens) and the amount of drainage at the trabecular meshwork (located at the base of the iris anteriorly, in the corner that the iris forms with the cornea). Could scleral lens wear impact this delicate balance? The take-home message for clinical practice is that scleral lenses could alter IOP to some degree. But definite conclusions cannot be drawn at this point based on the current evidence, the CLEAR paper states. Avoiding scleral lenses in patients who have progressive glaucoma seems to make sense but is not always easy. Sclerals are typically not worn ‘for fun’: there is usually a major indication to wear these lenses, and the benefits should be weighed against the risks – while monitoring visual fields and optic nerve head changes. But in some other cases, alternatives, including corneal GPs, hybrids or soft custom lenses, can potentially be considered. Whether lens design options, including non-symmetrical lens design, are beneficial and could alleviate the problem remains to be seen.

In closing

It has been quite a journey with scleral lenses over the last couple of decades, but it seems clear that ‘A Star Is Born’ in our specialty lens arena: scleral lenses. While the ocular surface shape issues ‘have been solved’ to a large degree, safety issues remain an important point of focus. Going backstage with scleral lenses, it seems like some of the bigger obstacles, including the oxygen debate, have now settled. Other problems such as MDF and conjunctival prolapse are a nuisance, but there are options to try to alleviate this; for example, aligning the scleral lens better with the ocular surface could alleviate those problems to some degree, but they cannot always be solved. Regarding MK – which is our biggest concern in contact lens practice, including scleral lens practice – as with any lens modality, that should have our greatest attention. Thicker lenses and an added (stagnant) fluid tear layer behind the lens are unavoidable and may be disadvantageous in this regard. But most important seems to be compliance and hygiene, including proper cleaning of the lenses, the lens cases and the lens applicators as well as avoiding any tap water use in the care regimen to avoid an infection and to provide the safest scleral lens wearing environment as much as possible. We can really make a difference as a joint responsibility: of the patient, the practice (eye care practitioner and staff) and the industry together.

In the next ‘episode’ in the trilogy on specialty lens safety, overnight orthokeratology will be highlighted. Stay tuned. Stay safe

Eef van der Worp, BOptom, PhD, FAAO, FIACLE, FBCLA, FSLS is an educator and researcher. He received his optometry degree from the Hogeschool van Utrecht in the Netherlands (NL) and has served as a head of the contact lens department at the school for over eight years. He received his PhD from the University of Maastricht (NL) in 2008.

He is a fellow of the AAO, IACLE, BCLA and the SLS. He is currently adjunct Professor at the University of Montreal University College of Optometry (CA) and adjunct assistant Professor at Pacific University College of Optometry (Oregon, USA). He lectures extensively worldwide and is a guest lecturer at a number of Universities in the US and Europe.

References

[1] DeNaeyer G, Sanders D, van der Worp E, Jedlicka J, Michaud L, Morrison S. Qualitative Assessment of Scleral Shape Patterns Using a New Wide Field Ocular Surface Elevation Topographer. JCLRS. 16 Nov 2017

[2] Van der Worp E. Safety First. Contact Lens Spectrum. April 2022;..-..

[3] Fisher D, Collins MJ, Vincent SJ. Fluid Reservoir Thickness and Corneal Edema during Open-eye Scleral Lens Wear. Optom Vis Sci. 2020 Sep;97(9):683-689. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001558. PMID: 32932398.

[4] Walker MK, Bergmanson JP, Miller WL, Marsack JD, Johnson LA. Complications and fitting challenges associated with scleral contact lenses: A review. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2016 Apr;39(2):88-96. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2015.08.003. Epub 2015 Sep 2. PMID: 26341076.

[5] Skidmore KV, Walker MK, Marsack JD, Bergmanson JPG, Miller WL. A measure of tear inflow in habitual scleral lens wearers with and without midday fogging. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2019 Feb;42(1):36-42. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2018.10.009. Epub 2018 Nov 16. PMID: 30455083; PMCID: PMC6340712.

[6] Fisher D, Collins MJ, Vincent SJ. Conjunctival prolapse during open eye scleral lens wear. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2021 Feb;44(1):115-119. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2020.09.001. Epub 2020 Oct 2. PMID: 33012674.

[7] Carracedo G, Wang Z, Serramito-Blanco M, Martin-Gil A, Carballo-Alvarez J, Pintor J. Ocular Surface Temperature During Scleral Lens Wearing in Patients With Keratoconus. Eye Contact Lens. 2017 Nov;43(6):346-351. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000273. PMID: 27203795.

[8] Macedo-de-Araújo RJ, Serramito-Blanco M, van der Worp E, Carracedo G, González-Méijome JM. Differences between Inferior and Superior Bulbar Conjunctiva Goblet Cells in Scleral Lens Wearers: A Pilot Study. Optom Vis Sci. 2020 Sep;97(9):726-731. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001575. PMID: 32941332.

[9] Van der Worp E. Safety First. Contact Lens Spectrum. April 2022: 28-33

[10] Barnett M, Courey C, Fadel D, Lee K, Michaud L, Montani G, van der Worp E, Vincent SJ, Walker M, Bilkhu P, Morgan PB. CLEAR – Scleral lenses. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2021 Apr;44(2):270-288. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2021.02.001. Epub 2021 Mar 25. PMID: 33775380.

[11] Shorter E, Schornack M, Harthan J, Nau A, Fogt J, Cao D, Nau C. Keratoconus Patient Satisfaction and Care Burden with Corneal Gas-permeable and Scleral Lenses. Optom Vis Sci. 2020 Sep;97(9):790-796. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001565. PMID: 32941334.

[12] Schornack MM, Pyle J, Patel SV. Scleral lenses in the management of ocular surface disease. Ophthalmology. 2014 Jul;121(7):1398-405. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.01.028. Epub 2014 Mar 14. PMID: 24630687.

[13] Kreps EO, Pesudovs K, Claerhout I, Koppen C. Mini-Scleral Lenses Improve Vision-Related Quality of Life in Keratoconus. Cornea. 2021 Jul 1;40(7):859-864. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002518. PMID: 32947413.

[14] Macedo-de-Araújo RJ, van der Worp E, González-Méijome JM. A one-year prospective study on scleral lens wear success. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020 Dec;43(6):553-561. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2019.10.140. Epub 2019 Nov 14. PMID: 31734087.