Vision impossible?

Holy grail aberrations

What I like about the contact lens field – as opposed to general medicine, for instance – is that we can ‘create things.’ Beautiful things. General medicine and eye care is more about dealing with existing conditions, while in the contact lens field, we can create vision. How cool is that?

We should be proud of what we have achieved as an industry, proud of the ultra-sophisticated lenses that we create to improve vision. The thing is, though, that the vision improvements with our lenses – notably rigid corneal lenses and scleral lenses – are so great that we usually don’t look further. But now that we have evolved from PMMA to super- and ultra-Dk lens materials, as well as from basic spherical back-surface designs to high-tech toric, quadrant-specific, octant-specific and free-form designs, it may be time ‘to go the extra mile’ and see what we can do beyond what standard lenses can do. Some patients can surely benefit from that. This is where higher-order aberrations come in. Are they the holy grail? Or is this ‘vision impossible?’

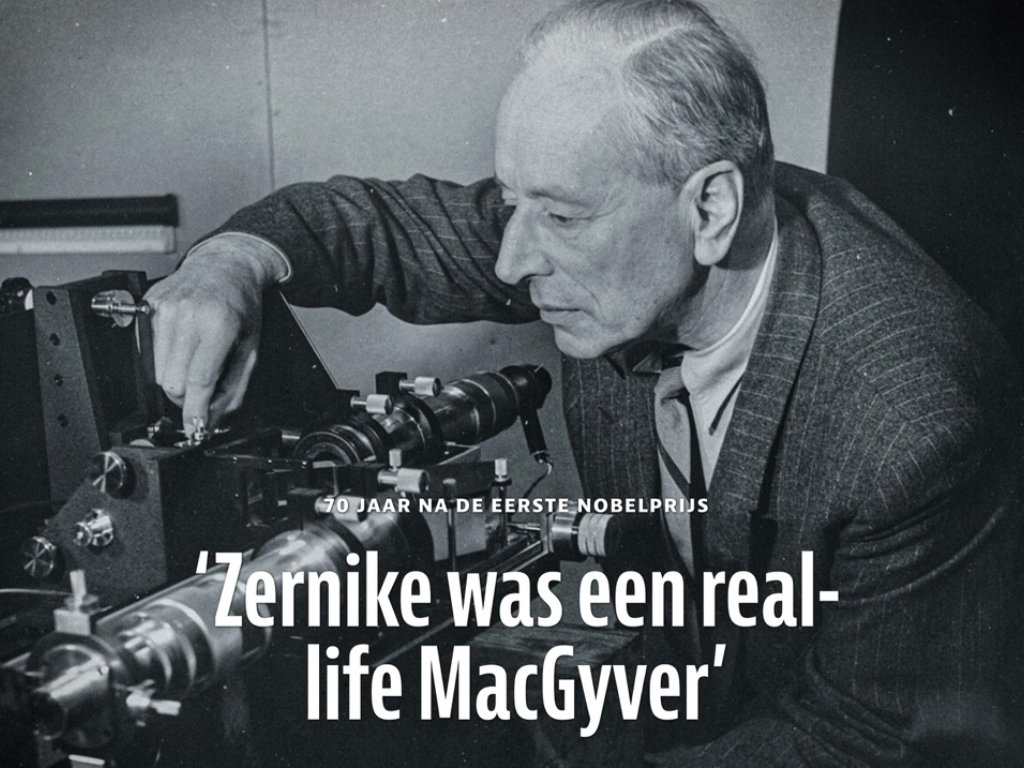

Frits Zernike

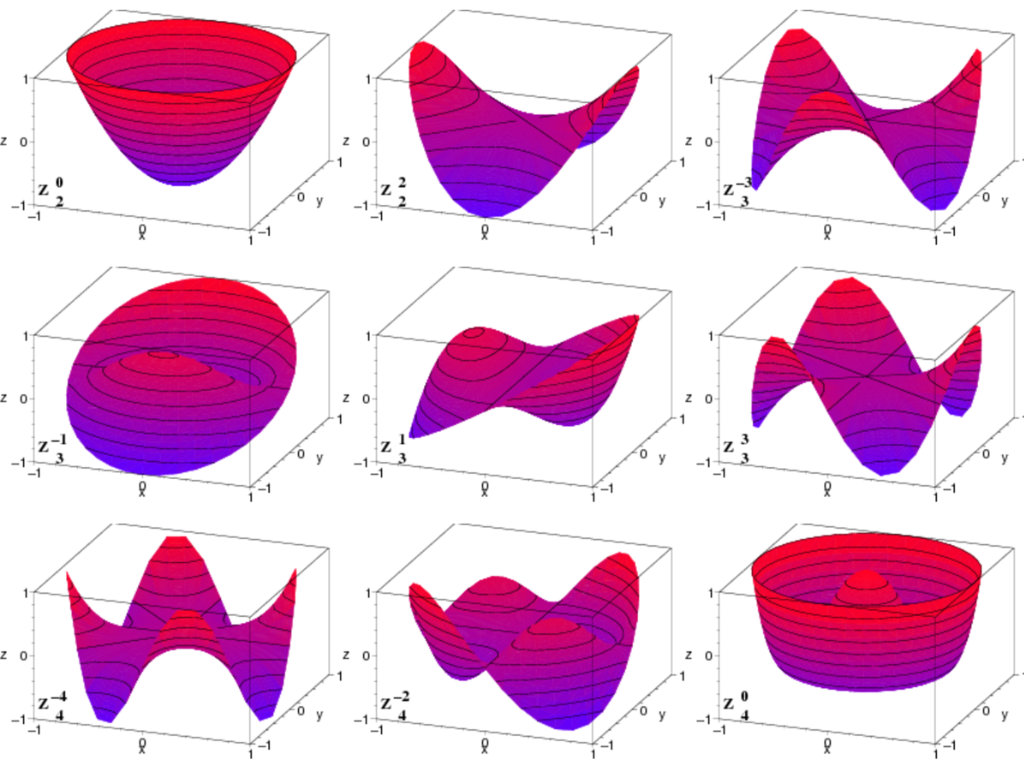

Let’s first see what these so-called ‘higher-order’ aberrations are. Why higher? Higher than what? This stems from a classification system by Dutch scientist Frits Zernike (16 July 1888 – 10 March 1966). On April 30, 1934, Zernike published an article in the journal Physics called “Beugungstheorie des Schneidenverfahrens und seiner verbesserten Form, der Phasenkontrastmethode.” It is basically unreadable for people outside the field of physics, but we can see this work as a dictionary for aberrations. The thing with aberrations is that there are too many (hundreds or even thousands if you want; in fact, the number of Zernike polynomials is infinite). Little imperfections in lenses can cause distinct distortions, especially if you want to see very far away (telescopes) or tiny things up close (microscopes).

Nobel prize

Zernike was a chemist by training, but back in his day (early 1900s), different disciplines were not as distinct and bordered off as they may be today. He was also interested in (and studied) physics and mathematics. All this really came in handy when he invented the phase-contrast microscope in 1933. While analyzing aberrations in circular pupils (such as those in lenses and microscopes), he introduced what we now call Zernike polynomials – a complete set of orthogonal functions. These provided a neat mathematical way to describe and quantify optical aberrations.

This work on representing aberrations led directly to his insights on phase effects in light waves. With this, he invented the phase contrast microscope, which allows us for the first time ever to see living cells. Before that time, you had to dye cells with color before you could analyze them, but that killed the cells (to dye is to die, in this case). With the phase-contrast microscope, we could now see the process of cells dividing, which was not possible up to then. The phase contrast microscope revolutionized biology. In 1953, Zernike received a Nobel prize for this development.

Christiaan Huygens

The good thing for us in the contact lens field is that we can focus on mostly the first two levels of Zernike higher-order polynomials: spherical aberration and coma (comatic aberration). Higher orders than that are typically not relevant, as we are dealing with human tissue, which is never as optically sound as lenses used for microscopes.

Regarding aspheric lenses, in the mid-17th century, Rene Descartes (who lived in Amsterdam at the time) and Christiaan Huygens already had described (Descartes) and made (Huygens) aspheric lens surfaces to improve the optical quality. Because of that, Huygens was the first ever to see the ‘ring’ around Saturn in 1655. Earlier, Galileo (1610) had seen odd “handles” or “ears” on Saturn with his small telescope, but he couldn’t resolve what they were. But in March 1655, using a much better telescope with lenses he had designed and ground himself, Huygens observed Saturn and realized it was surrounded by a thin, flat ring, tilted with respect to the ecliptic and not touching the planet. The Italians figured ‘the air in Holland must be clearer” to see that level of detail. But it was not the air – it was the higher quality of the lenses Huygens used. As a side note, but still interesting, the famous philosopher Baruch de Spinoza of the Enlightenment, whose radical ideas on religion, politics, and human freedom made him one of the most influential and controversial thinkers in Western philosophy, was also a lens grinder who actually worked with Huygens. Huygens was ‘very impressed’ by the hand-ground lenses Spinoza created.

An easy aberration

Back to the topic: spherical aberration is an ‘easy aberration,’ because it is (as the name denotes) spherical in nature, so it is a ‘rotationally symmetrical’ aberration. This means it is fairly easy to apply to contact lens surfaces, for instance; you don’t need any form or type of stabilization because the aberration is 360 degrees around. All you need is the current aberrations of the eye – or you need the aberrations of the lens (corneal or scleral) that induce spherical aberrations, then you can apply the opposite aberration on the front.

For scleral lenses, the aspheric front optics can ‘solve’ some, or a large degree, of the aberrations induced by the lens. If you want the ‘full’ effect of spherical aberration for a given patient, the best course of action would be to place a lens on the eye and let it settle, then measure aberrations over the lens. Anything that is ‘left over’ can then be added to the front surface, if desired.

For this to work, the lens must be stable on the eye, not move and be centered over the visual axis of the eye. Any form of decentration or movement eliminates the effect of the aberration correction. So yes – this is ‘correction of higher-order aberration,’ but it can be applied to all lenses.

Positive about negative spherical aberration

In short, there are only two types of spherical aberration (both rotationally symmetrical): positive spherical aberration (in which the edge rays focus closer than the central rays) and negative spherical aberration (in which the edge rays focus farther than the central rays). The average human eye typically has positive spherical aberration, which can be corrected with negative aberrations in the lens. In fact, many soft lens manufacturers add the average amount of spherical aberration present in the general population to their standard lenses.

Is this ‘higher-order aberration correction’? It may be, but only for the most standard of eyes. If your eye has or needs more negative or positive spherical aberrations (because that is the nature of the eye), then this lens would not be your best option, and it would be the opposite of higher-order aberration correction. In short, it can be a form of higher-order aberration correction, but it certainly is not a customized one. For that you would need to measure the aberration of the eye and then apply it to the front lens surface for that particular person. It still can be done in a rotationally symmetrical way, without stabilization, etc. – as long as the lens centers well over the line of sight (which is not the geometrical center of the cornea, by the way).

In a COMA

It gets more difficult with the next higher-order aberration in eyecare: comatic aberration (coma). This is another type of optical aberration that shows up when you look at a point of light and instead of seeing a neat little dot, it looks like a comet with a tail – that’s why it’s called coma. Positive coma is when the bright core of the image is closer to the optical axis (center), and the “tail” stretches away from the center. In negative coma, the bright core is further out, and the tail stretches toward the center – so the comet tail points inward, toward the middle of the picture. When we describe aberrations using Zernike polynomials, coma shows up as two distinct types: horizontal coma (X-coma), which corresponds to asymmetry in the x-direction (left–right), and vertical coma (Y-coma), which corresponds to asymmetry in the y-direction (up–down).

Granted, higher-order aberrations can be quite complex, and some people get comatose just looking at them. But in essence, when it comes to coma there are positive, negative, vertical and horizontal (four types in all) that are represented in Zernike’s octagonal ‘dictionary.’ It gets more complex because the orientation of the coma can be at an angle (not just pure vertical or pure horizontal). But clinically and in research, we usually break it down into horizontal versus vertical, with each having positive or negative polarity.

For the completeness of this article, there is a third aberration in eye care that should be mentioned: trefoil. Trefoil distorts vision in a pattern that looks like a three-pointed star (similar to a cloverleaf or the “Mercedes-Benz” logo), but it is less common. Spherical aberration and coma are the most common higher-order aberrations in the average eye, and while trefoil can show up in diseased or surgically altered corneas (such as keratoconus, scars, or post-LASIK), it is also harder to correct with optical designs. A small misalignment (rotation of the lens, decentration) can make the correction ineffective or even introduce new distortions. Therefore, trefoil is less commonly mentioned and used compared to the other two primary aberrations in the field of eyecare.

Fluid column

As said earlier, we need to distinguish between aberrations induced by the eye (in our case, usually the cornea) and aberrations induced by the lens. As an example, vertical coma is the hallmark of keratoconus. The cone is usually off-center (often downward), so light gets bent unevenly, producing a “comet-tail” blur. Vertical coma is usually much more common in keratoconus than in normal eyes.

At the same time, if a scleral lens isn’t perfectly centered, the tear fluid reservoir is thicker on one side than the other. This imbalance induces coma-like aberrations, often vertical coma (similar to keratoconus itself), and this is usually the main aberration induced.

Cylindrical over-refraction in scleral lens wear

The importance of the fluid column optically in scleral lens wear is not very well understood. Decentration speaks for itself, with potential prismatic effects (with inferior decentration, sometimes significant ‘prism-down’ effects are induced). But there is more. It is intriguing that if you fit normal eyes (no corneal pathology) with scleral lenses (for instance, a classroom of 30 third-year optometry students on a Monday morning), you get a huge amount of cylindrical over-refractions (while no cylinder is present in their prescriptions or on their corneas). Why? It is a little bit of a mystery, to be honest, but probably the ‘tilt’ of a scleral lens plays a role in addition to the decentration and prismatic effect. The fact is, the fluid column and the way a lens lands on the eye play a role in the optical outcome in scleral lens wear. Many large practices sometimes report front-toric lens additions in up to 50% of the lenses they dispense. This is a huge number that cannot be explained only by looking at the pathology (such as keratoconus) that is often the underlying indication for the scleral lens fit.

Las Vegas

Vision impossible? Due to the work of Frits and the contact lens industry, correcting aberrations is not a utopia anymore but a reality. However, it’s a reality that needs to be viewed with caution. We should be careful not to get carried away. Not all higher-order aberrations are worthwhile to correct, and we need to be sensible in using a term for what is meant: customized higher-order aberration correction, or something else. And there is also the ‘neural adaption’ factor, which is too far off-topic to discuss here.

But having said all that, this topic of aberration correction is typically very high on the agenda of any specialty lens symposium worldwide today, and this will certainly be the case at the 2026 Global Specialty Lens Symposium in Las Vegas on January 7-11; the topic of applying this to specialty contact lenses shall be discussed and explored in depth and in detail, just like aberrations themselves.

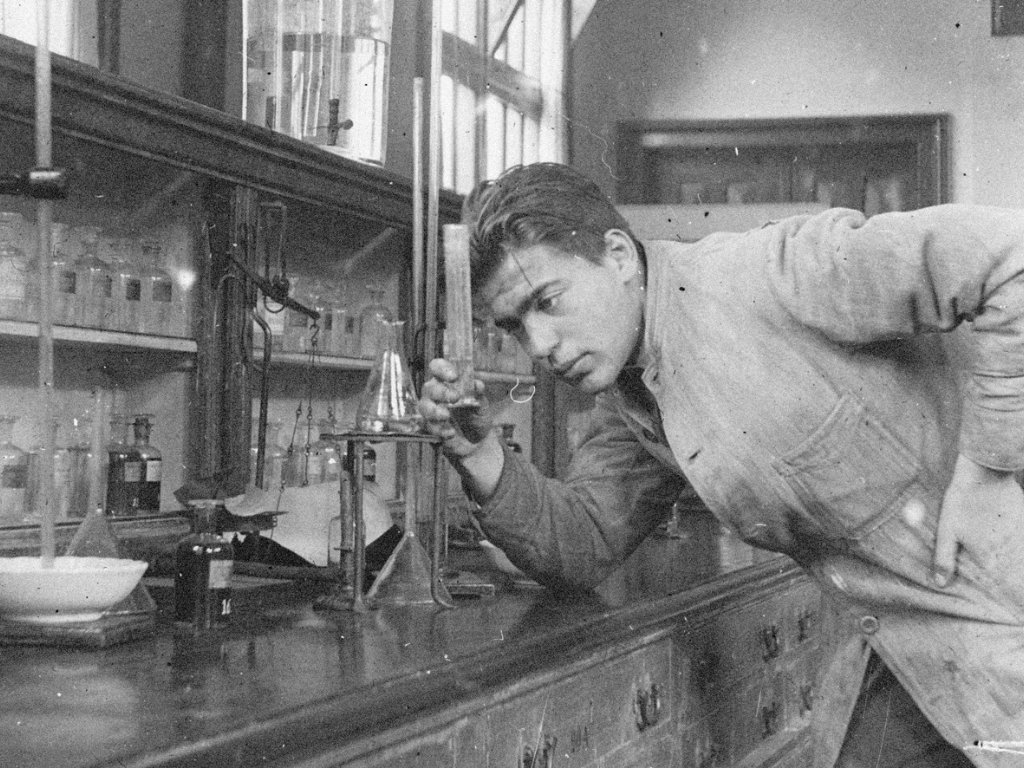

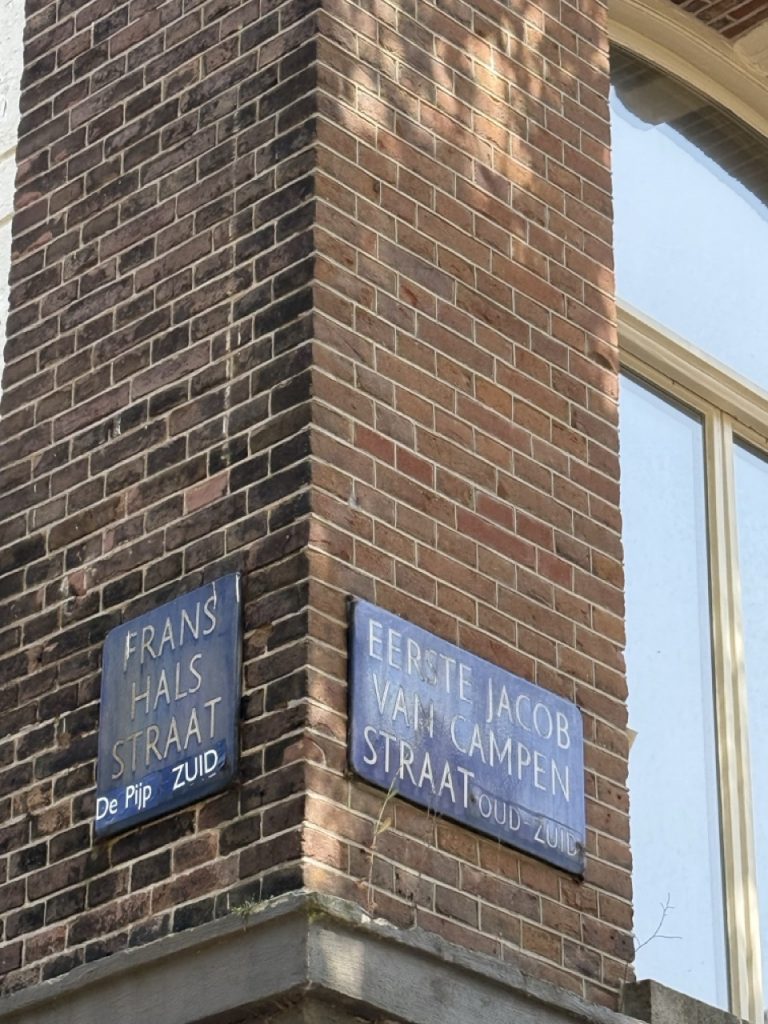

The Amsterdam School

I live in the heart of Amsterdam, and what I recently learned is that Frits Zernike was born and raised just a few blocks from my house: on the corner of the Jacob van Campenstraat and the Frans Halsstraat in a hip neighborhood (now) of Amsterdam called ‘the pijp.’ He attended the elementary school on the same street and went to high school/college at a school a stone’s throw away from his house. That school (built in 1894) is now a beautiful boutique hotel in the style of the old school building it had been (The College Hotel). What is nicely done is that many details in the hotel remind us of the educational institution it once was: the library is still (a ceremonial) library, the room numbers are simple mathematical equations, and the carpet contains many scholastic references, like chemical formulas. Speaking of which, Zernike started as a chemist as said. The bar in The College Hotel is the exact place where the chemistry lab was located (see image). So, if you are ever in Amsterdam, consider staying at ‘Frits school’ and join me in that bar, and we’ll drink to Zernike, to higher-order aberrations and the beautiful work we do in our industry to help see patients better.